Table of contents

1. Introduction

2. Slovakia during the 2nd World War

3. Operation Anthropoid

3.1. Exiles

3.2. Prelude

3.3. Preparations

3.4. Assassination

4. Aftermath

5. Epilogue

6. References

1. Introduction

During the apex of the global pandemic in 2020 a remote family member of mine passed away quietly in a nursing home where she had been living in her last years. She was well over ninety, and due to the circumstances at that time only a very small group of people was allowed to attend the funeral.

Like so many other families in Central Europe during the first half of the 20th century, we had to endure war, war captivity and expulsion from our homes, so the manner of my relative’s bleak and furtive funeral made us all the more aware that it is just a matter of few years that the remaining survivors who had consciously experienced the era of Nazi Germany will all have passed away.

My deceased relative was presumably the last contemporary witness in my big and widely dispersed family, and I remember vividly some of her accounts of gruesome bombing nights in Hamburg in the World War’s final stages.

As in case of the Great Depression and the 1st World War, future scholars and descendants of the war generation will soon have to fall back on books and museums for learning about the 2nd World War, the most terrible and tragic event of the 20th century.

2. Slovakia during the 2nd World War

Over the course of the last decade I’ve developed a deep interest in the culture and the history of Germany’s eastern neighbors, not least on grounds of my own family history I’ve referred to every so often on this website.

As for Poland, Czechia and Slovakia, I fortunately had plenty of opportunities in recent years to broaden my horizons through traveling, and to absorb every information I could find.

Taking a closer look at those three countries, or at the Eastern European countries in general during the 2nd World War, the involvement of Slovakia deviates from the usual pattern of Nazi invasion, exploitation of resources and labor, and mass executions from day one as it was the case in Poland or Russia.

There was also no outright annexation as it was the case for Czechia, which was morphed into the so called “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” in 1939 (until the “Munich Agreement” in 1938, there existed the state of Czechoslovakia).

As Germany invaded Poland and (later) the Soviet Union, Slovakia even provided some troops and logistics as a de-facto vassal state of Nazi Germany (in some regards similar to Hungary), but was nonetheless able to keep independence and sovereignty to some degree.

The small country had more or less adjusted itself with its mighty neighbor, and the Slovak leaders were realists enough to see that there was not much space for political maneuvers considering the latent threat of being invaded and swallowed up as well1.

However, this state of affairs wasn’t tolerable for many Slovak patriots, especially for soldiers who had served in the now demobilized Czechoslovakian army. For them, it was out of the question not to fight against Nazi oppression.

3. Operation Anthropoid

3.1. Exiles

The Slovak Jozef Gabčík, born in 1912 in north Slovakia near the city of Žilina, was a sergeant in the Czechoslovakian exile army, stationed and trained in Great Britain from 1940 on along with many fellow Slovaks and Czechs.

With an actual craftsmanship background and knowledge about tricky machinery and chemistry acquired during his industry employments, he seemed a natural aspirant for underground work: carrying out sabotage acts, handling intricate weapons, initiating subversive actions that demanded practical ingenuity.

Being already an experienced and decorated veteran who had seen several battlefields on the continent, he distinguished himself in the grueling commando training supervised by Czech and British intelligence officers.

Having the required physical and mental profile, he volunteered for special duties as a paratrooper in the Protectorate probably knowing that the odds to die during such missions were unreasonably high.

3.2. Prelude

The Czechoslovak sabotage and assassination teams which were by and by dropped over the Protectorate in 1941 and 1942 were organized in very small combat groups, consisting never of more than three paratroopers (see Appendix 2 in reference 12). The time intervals between drops of different combat groups were also dramatically long, often months rather than weeks.

The primary reasons were the geographical circumstances at this stage of the war: by comparison to (for example) France with its closeness to the British islands, it was very dangerous and expensive to establish, maintain and supply a large underground network from outside in a territory that bordered Slovakia, the occupied Poland and Nazi Germany itself.

Jozef Gabčík was assigned to a parachute group named Anthropoid, which comprised only two soldiers. The second parachutist in the team was the Czech Jan Kubiš, born 1913 in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands.

It was by no means an accident that the team comprised a Czech and a Slovak paratrooper.

The objective for what they were to be dropped in December 1941 was the assassination of the most important German official (the so called Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor) in the Protectorate, SS-General Reinhard Heydrich.

The agents who should carry out this top-secret mission had to represent Czechoslovakia, not just Slovakia or just Czechia.

3.3. Preparations

On 27 May 1942, after months of thorough preparation and moving around through different hiding places in Bohemia, Gabčík and Kubiš were taking position at a sharp turn in Holešovice, a bustling district in the north of Prague where the river Moldau meanders through the city.

They had a set of different weapons at their disposal, provided by the British military: a simple and cheap submachine gun (whose questionable reliability would almost prove disastrous), two specially designed anti-vehicle grenades, pistols.

An additional element of improvisation is an inherent feature of clandestine operations, beside the vital necessities of an in-detail planning.

For it wasn’t a suicide mission, the possible locations for the assassination had to offer an opportunity to flee quickly into a hiding place after the attack.

The resistance had to compile a pattern of routines and habits of the SS-General as preliminary work. It was decided long in advance that Heydrich has to be attacked in his official car on his way to work, hence knowledge of his daily movements was essential (yet it was well-known that he never ordered additional SS-guards as escort, and he and his driver had just their pistols for self-defense).

The disadvantage of attacking a moving target was to be made up for by the aforementioned different kinds of attack devices: if the ambush with the submachine gun was for some reason unsuccessful, the grenades were at hand to finish the job.

3.4. Assassination

Despite the thorough preparation and the cold-blooded determination of the assassins, the attack itself was on the brink of being a complete disaster.

Gabčík’s submachine gun jammed at the crucial moment as the car slowed down right in front of him. As Kubiš then tossed one of the grenades he misjudged his throw: instead of landing inside the open Mercedes-Benz, it landed next to the right rear wheel and injured the Czech himself as it detonated.

The dazzled and momentarily stunned, but apparently not seriously hurt Heydrich and his driver went after their attackers, trying to shot at them with their pistols.

With some luck, Gabčík and Kubiš managed to escape in the general confusion, exchanging gun shots with the SS-General while getting rid of what was left of their equipment.

It seemed a bitter failure for the assassins and the Czechoslovakian resistance as a whole.

4. Aftermath

Unbeknownst to the assassins, the blast of the grenade had seriously injured Heydrich. He died a few days after the attack in a hospital in Prague, most likely due to an infection caused by fragments of the car’s seats which penetrated his lower torso.

However, the success of the Czechoslovakian resistance assisted and outfitted by the British military was paid with the ultimate price.

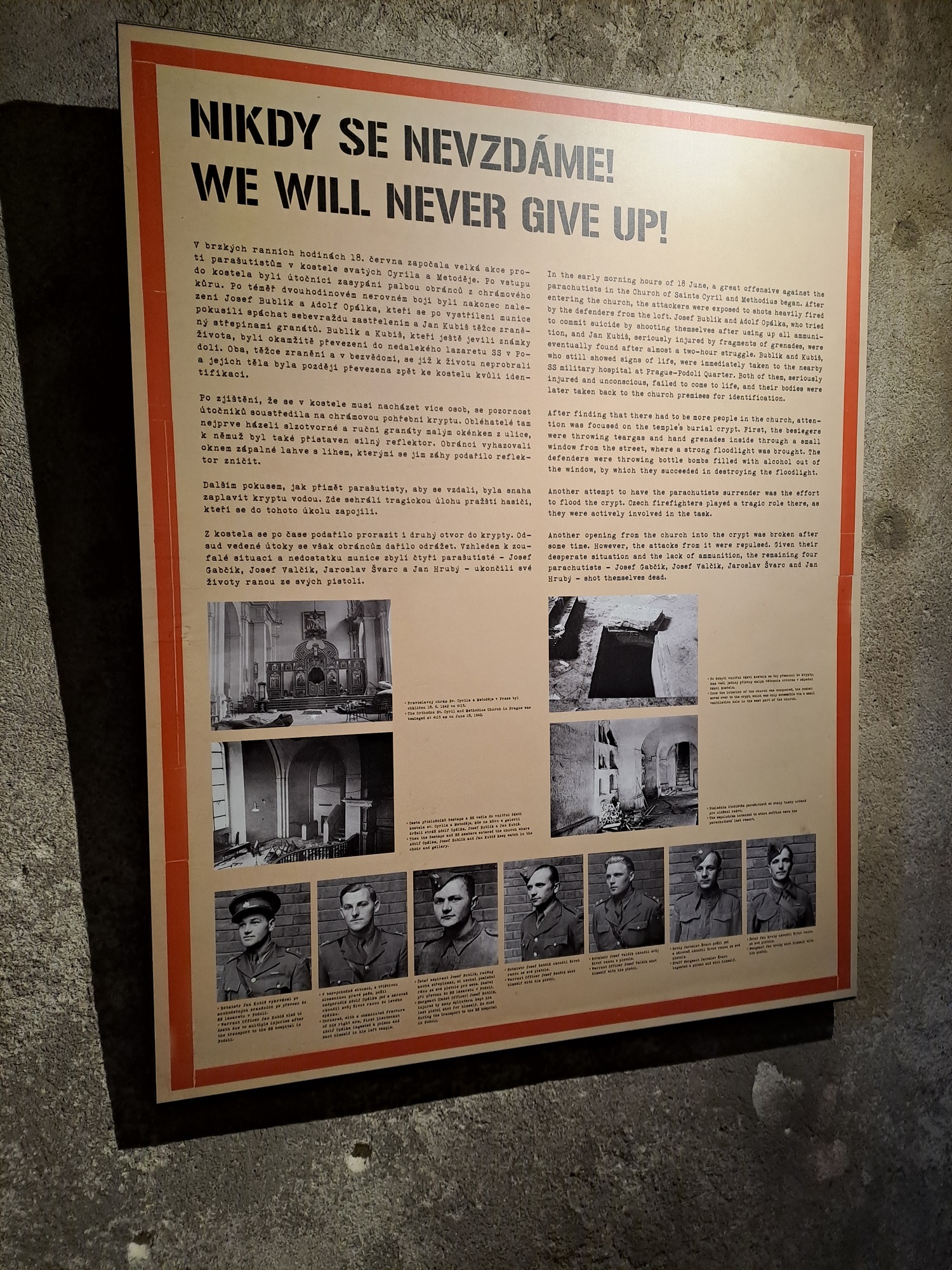

Despite being untraceable for the Gestapo for about three weeks, the pressure of Nazi terror and reprisals eventually led to the betrayal from a former comrade and to the hiding place of the assassins and their companions: the orthodox Saints Cyril and Methodius Cathedral in the New Town of Prague.

The traces of the desperate and lopsided final battle are still visible today. Heavily armed Germans besieged and shot ruthlessly at the church for hours, though the military commanders wanted to capture the agents alive rather than dead.

As the SS was about to storm the edifice after Kubiš had lost his life already alongside with two other Czechs, the remaining four agents committed suicide with their last bullets to avoid capture.

Gabčík shot himself in the head, cowering in the Krypta (Crypt) as one of the very last still alive.

5. Epilogue

Visiting the historical sites in Prague, the Crypt in the Saints Cyril and Methodius Cathedral in particular, is a humbling experience.

Jozef Gabčík and the other agents in the Cathedral learned from their contacts a couple of days before their own death that Heydrich had fallen into a coma and died as a result of the bomb inflicted wounds.

What they of course couldn’t know is that the assassination of the SS-General remained the sole successful operation of this kind during the entire war.

Whether it was worth the high price has been a matter of debate, since not only the agents died in the aftermath but thousands of Czech civilians as well (with the most infamous war crime committed against the village of Lidice).

One has to admire the assassins and their heroism regardless. They could have chosen to stay in their comparatively safe spot in England, but they wanted to fight, knowing the chances to survive were as low as they can get.

6. References

6.1 Books

1. The assassination of Reinhard Heydrich – Callum MacDonald, Birlinn Limited 1989; ISBN 978-1-84341-036-2

2. VHU PRAHA – Military History Institute Prague

6.2 Footnotes

1 this indeed took place in 1944 after the Slovak National Uprising and the desperate war situation for the German Reich

2 that book was one main source for this article